Largest city in Kansas, United States

Not to be confused with Wichita County, Kansas.

City and county seat in Kansas, United States

|

Wichita, Kansas

|

Exploration Place science museum

|

Flag

Seal

Logo

|

| Nickname(s):

Air Capital of the World,[1] ICT[2]

|

Location within Sedgwick County and Kansas

|

Interactive map of Wichita

|

| Coordinates:

37°41′20″N 97°20′10″W / 37.68889°N 97.33611°W / 37.68889; -97.33611[3] |

| Country |

United States |

| State |

Kansas |

| County |

Sedgwick |

| Founded |

1868 |

| Incorporated |

1870 |

| Named for |

Wichita people |

| • Type |

Council–manager |

| • Mayor |

Lily Wu (L) |

| • City Manager |

Robert Layton |

|

• City and county seat

|

166.52 sq mi (431.28 km2) |

| • Land |

161.99 sq mi (419.55 km2) |

| • Water |

4.53 sq mi (11.73 km2) |

| Elevation

[3]

|

1,303 ft (397 m) |

|

• City and county seat

|

397,532 |

|

|

396,119 |

| • Rank |

51st in the United States

1st in Kansas |

| • Density |

2,454.05/sq mi (947.52/km2) |

| • Urban

|

500,231 (US: 84th) |

| • Urban density |

2,205.2/sq mi (851.4/km2) |

| • Metro

[8]

|

647,919 (US: 93rd) |

| Demonym |

Wichitan |

| Time zone |

UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) |

UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

67201–67221, 67223, 67226–67228, 67230, 67232, 67235, 67260, 67275–67278[9]

|

| Area code |

316 |

| FIPS code |

20-79000 [3] |

| GNIS ID |

473862 [3] |

| Website |

wichita.gov |

Wichita ( WITCH-ih-taw)[10] is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Sedgwick County.[3] As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 397,532.[5][6] The Wichita metro area had a population of 647,610 in 2020.[8] It is located in south-central Kansas on the Arkansas River.[3]

Wichita began as a trading post on the Chisholm Trail in the 1860s and was incorporated as a city in 1870. It became a destination for cattle drives traveling north from Texas to Kansas railroads, earning it the nickname "Cowtown".[11][12] Wyatt Earp served as a police officer in Wichita for around one year before going to Dodge City.

In the 1920s and 1930s, businessmen and aeronautical engineers established aircraft manufacturing companies in Wichita, including Beechcraft, Cessna, and Stearman Aircraft. The city became an aircraft production hub known as "The Air Capital of the World".[13][14] Textron Aviation, Learjet, Airbus, and Boeing/Spirit AeroSystems continue to operate design and manufacturing facilities in Wichita, and the city remains a major center of the American aircraft industry. Several airports located within the city of Wichita include McConnell Air Force Base,[15][16] Colonel James Jabara Airport, and Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport, the largest airport in Kansas.

As an industrial hub, Wichita is a regional center of culture, media, and trade. It hosts several universities, large museums, theaters, parks, shopping centers, and entertainment venues, most notably Intrust Bank Arena and Century II Performing Arts & Convention Center. The city's Old Cowtown Museum maintains historical artifacts and exhibits the city's early history. Wichita State University is the third-largest post-secondary institution in the state.

History

[edit]

Main articles: History of Wichita, Kansas and Timeline of Wichita, Kansas

Early history

[edit]

See also: Early Kansas History

Archaeological evidence indicates human habitation near the confluence of the Arkansas and Little Arkansas Rivers, the site of present-day Wichita, as early as 3000 BC.[17] In 1541, a Spanish expedition led by explorer Francisco Vázquez de Coronado found the area populated by the Quivira, or Wichita, people. Conflict with the Osage in the 1750s drove the Wichita further south.[18] Prior to European settlement of the region, the site was in the territory of the Kiowa.[19]

19th century

[edit]

Darius Sales Munger House, built in 1868, is the oldest surviving building in Wichita (at Old Cowtown Museum).[20]

Darius Sales Munger House, built in 1868, is the oldest surviving building in Wichita (at Old Cowtown Museum).[20]

Claimed first by France as part of Louisiana and later acquired by the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, it became part of Kansas Territory in 1854 and then the state of Kansas in 1861.[21][22]

The Wichita people returned in 1863, driven from their land in Indian Territory by Confederate forces in the American Civil War, and established a settlement on the banks of the Little Arkansas.[23][24][25] During this period, trader Jesse Chisholm established a trading post at the site, one of several along a trail extending south to Texas which became known as the Chisholm Trail.[26] In 1867, after the war, the Wichita returned to Indian Territory.[23]

In 1868, trader James R. Mead was among a group of investors who established a town company, and surveyor Darius Munger built a log structure for the company to serve as a hotel, community center, and post office.[27][28] Business opportunities attracted area hunters and traders, and a new settlement began to form. That summer, Mead and others organized the Wichita Town Company, naming the settlement after the Wichita tribe.[24] In 1870, Munger and German immigrant William "Dutch Bill" Greiffenstein filed plats laying out the city's first streets.[28] Wichita formally incorporated as a city on July 21, 1870.[27]

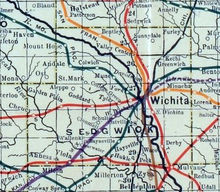

A 1915 railroad map of Sedgwick County, showing many railroads that previously passed through Wichita

A 1915 railroad map of Sedgwick County, showing many railroads that previously passed through Wichita

Wichita's position on the Chisholm Trail made it a destination for cattle drives traveling north from Texas to access railroads, which led to markets in eastern U.S. cities.[26][29] The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway reached the city in 1872.[30] As a result, Wichita became a railhead for the cattle drives, earning it the nickname "Cowtown".[26][29] Across the Arkansas River, the town of Delano became an entertainment destination for cattlemen thanks to its saloons, brothels, and lack of law enforcement.[31]

James Earp ran a brothel with his wife Nellie "Bessie" Ketchum. His brother Wyatt was likely a pimp, although historian Gary L. Roberts believes that he was an enforcer or bouncer.[32] Local arrest records show that Earp's common-law wife Sally and James' wife Nellie managed a brothel there from early 1874 to the middle of 1876.[33] The area had a reputation for violence until lawmen like Wyatt stepped up enforcement, who officially joined the Wichita marshal's office on April 21, 1875. He was hired after the election of Mike Meagher as city marshal, making $100 per month.[26][29] By the middle of the decade, the cattle trade had moved west to Dodge City. Wichita annexed Delano in 1880.[31]

Rapid immigration resulted in a speculative land boom in the late 1880s, stimulating further expansion of the city. Fairmount College, which eventually grew into Wichita State University, opened in 1886; Garfield University, which eventually became Friends University, opened in 1887.[34][35] By 1890, Wichita had become the third-largest city in the state after Kansas City, and Topeka, with a population of nearly 24,000.[36] After the boom, however, the city entered an economic recession, and many of the original settlers went bankrupt.[37]

20th century

[edit]

In 1914 and 1915, deposits of oil and natural gas were discovered in nearby Butler County. This triggered another economic boom in Wichita as producers established refineries, fueling stations, and headquarters in the city.[38] By 1917, five operating refineries were in Wichita, with another seven built in the 1920s.[39] The careers and fortunes of future oil moguls Archibald Derby, who later founded Derby Oil, and Fred C. Koch, who established what would become Koch Industries, both began in Wichita during this period.[38][40]

The money generated by the oil boom enabled local entrepreneurs to invest in the nascent airplane-manufacturing industry. In 1917, Clyde Cessna built his Cessna Comet in Wichita, the first aircraft built in the city. In 1920, two local oilmen invited Chicago aircraft builder Emil "Matty" Laird to manufacture his designs in Wichita, leading to the formation of the Swallow Airplane Company. Two early Swallow employees, Lloyd Stearman and Walter Beech, went on to found two prominent Wichita-based companies, Stearman Aircraft in 1926 and Beechcraft in 1932, respectively. Cessna, meanwhile, started his own company in Wichita in 1927.[1] The city became such a center of the industry that the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce dubbed it the "Air Capital of the World" in 1929.[13][41][42]

Boeing B-29 assembly line (1944)

Boeing B-29 assembly line (1944)

Over the following decades, aviation and aircraft manufacturing continued to drive expansion of the city. In 1934, Stearman's Wichita facilities became part of Boeing, which would become the city's largest employer.[43] Initial construction of Wichita Municipal Airport finished southeast of the city in 1935. During World War II, the site hosted Wichita Army Airfield and Boeing Airplane Company Plant No. 1.[44] The city experienced a population explosion during the war when it became a major manufacturing center for the Boeing B-29 bomber. The wartime city quickly grew from 110,000 to 184,000 residents, drawing aircraft workers from throughout the central U.S.[13][45] In 1951, the U.S. Air Force announced plans to assume control of the airport to establish McConnell Air Force Base. By 1954, all nonmilitary air traffic had shifted to the new Wichita Mid-Continent Airport west of the city.[44] In 1962, Lear Jet Corporation opened with its plant adjacent to the new airport.[46]

The original Pizza Hut building, which was moved to the campus of Wichita State University (2004)

The original Pizza Hut building, which was moved to the campus of Wichita State University (2004)

Throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries, several other prominent businesses and brands had their origins in Wichita. A. A. Hyde founded health-care products maker Mentholatum in Wichita in 1889.[47][48] Sporting goods and camping-gear retailer Coleman started in the city in the early 1900s.[47][49] A number of fast-food franchises started in Wichita, beginning with White Castle in 1921 and followed by many more in the 1950s and 1960s including Pizza Hut in 1958. In the 1970s and 1980s, the city became a regional center of health care and medical research.[47][50]

Wichita has been a focal point of national political controversy multiple times in its history. In 1900, famous temperance extremist Carrie Nation struck in Wichita upon learning the city was not enforcing Kansas's prohibition ordinance.[47] The Dockum Drug Store sit-in took place in the city in 1958 with protesters pushing for desegregation.[51] In 1991, thousands of anti-abortion protesters blockaded and held sit-ins at Wichita abortion clinics, particularly the clinic of George Tiller.[52] Tiller was later murdered in Wichita by Scott Roeder in 2009.[53]

21st century

[edit]

Except for a slow period in the 1970s, Wichita has continued to grow steadily into the 21st century.[36] In the late 1990s and 2000s, the city government and local organizations began collaborating to redevelop downtown Wichita and older neighborhoods in the city.[28][31][54] Intrust Bank Arena opened downtown in 2010.[55]

Boeing ended its operations in Wichita in 2014.[56] However, the city remains a national center of aircraft manufacturing with other companies including Spirit AeroSystems and Airbus maintaining facilities in Wichita.[27][57]

Wichita Mid-Continent Airport was officially renamed Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport after the Kansas native and U.S. President in 2015.[58]

Geography

[edit]

Downtown Wichita viewed from the west bank of the Arkansas River (2010)

Downtown Wichita viewed from the west bank of the Arkansas River (2010)

Wichita is in south-central Kansas at the junction of Interstate 35 and U.S. Route 54.[59] Part of the Midwestern United States, it is 157 mi (253 km) north of Oklahoma City, 181 mi (291 km) southwest of Kansas City, and 439 mi (707 km) east-southeast of Denver.[60]

The city lies on the Arkansas River near the western edge of the Flint Hills in the Wellington-McPherson Lowlands region of the Great Plains.[61] The area's topography is characterized by the broad alluvial plain of the Arkansas River valley and the moderately rolling slopes that rise to the higher lands on either side.[62][63]

The Arkansas follows a winding course, south-southeast through Wichita, roughly bisecting the city. It is joined along its course by several tributaries, all of which flow generally south. The largest is the Little Arkansas River, which enters the city from the north and joins the Arkansas immediately west of downtown. Further east lies Chisholm Creek, which joins the Arkansas in the far southern part of the city. The Chisholm's own tributaries drain much of the city's eastern half; these include the creek's West, Middle, and East Forks, as well as further south, Gypsum Creek. The Gypsum is fed by its own tributary, Dry Creek. Two more of the Arkansas's tributaries lie west of its course; from east to west, these are Big Slough Creek and Cowskin Creek. Both run south through the western part of the city. Fourmile Creek, a tributary of the Walnut River, flows south through the far eastern part of the city.[64]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 163.59 sq mi (423.70 km2), of which 4.30 sq mi (11.14 km2) are covered by water.[65]

As the core of the Wichita metropolitan area, the city is surrounded by suburbs. Bordering Wichita on the north are, from west to east, Valley Center, Park City, Kechi, and Bel Aire. Enclosed within east-central Wichita is Eastborough. Adjacent to the city's east side is Andover. McConnell Air Force Base is in the extreme southeast corner of the city. To the south, from east to west, lie Derby and Haysville. Goddard and Maize border Wichita to the west and northwest, respectively.[66]

Climate

[edit]

Climatic influences on weather

[edit]

Wichita lies within the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen Cfa), typically experiencing hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters. Located on the Great Plains, far from any large moderating influences such as mountains or large bodies of water, Wichita often experiences severe weather with thunderstorms occurring frequently during the spring and summer. These occasionally bring large hail and frequent lightning. Particularly destructive ones have struck the Wichita area several times in the course of its history - in September 1965, during the Andover, Kansas tornado outbreak of April 1991, and during the Oklahoma tornado outbreak of May 1999.[67][68][69] Winters are cold and dry; since Wichita is roughly midway between Canada and the Gulf of Mexico, cold spells and warm spells are equally frequent. Warm air masses from the Gulf of Mexico can raise midwinter temperatures into the 50s and even 60s (°F), while cold-air masses from the Arctic can occasionally plunge the temperature below 0 °F. Wind speed in the city averages 13 mph (21 km/h).[70] On average, January is the coldest month (and the driest), July the hottest, and May the wettest.

Weather data

[edit]

Climate chart for Wichita

Climate chart for Wichita

The average temperature in the city is 57.7 °F (14.3 °C).[71] Over the course of a year, the monthly daily average temperature ranges from 33.2 °F (0.7 °C) in January to 81.5 °F (27.5 °C) in July. The high temperature reaches or exceeds 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 65 days a year and 100 °F (38 °C) an average of 12 days a year. The minimum temperature falls to or below 10 °F (−12 °C) on an average 7.7 days a year. The hottest temperature recorded in Wichita was 114 °F (46 °C) in 1936; the coldest temperature recorded was −22 °F (−30 °C) on February 12, 1899. Readings as low as −17 °F (−27 °C) and as high as 111 °F (44 °C) occurred as recently as February 16, 2021, and July 29–30, 2012, respectively.[72] Wichita receives on average about 34.31 inches (871 mm) of precipitation a year, most of which falls in the warmer months, and experiences 87 days of measurable precipitation. The average relative humidity is 80% in the morning and 49% in the evening.[70] Annual snowfall averages 12.7 inches (32 cm). Measurable snowfall occurs an average of nine days per year with at least an inch of snow falling on four of those days. Snow depth of at least an inch occurs an average of 12 days per year.[71] The average window for freezing temperatures is October 25 through April 9.[72]

| Climate data for Wichita, Kansas (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1888–present)[b] |

| Month |

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

Year |

| Record high °F (°C) |

75

(24) |

87

(31) |

92

(33) |

98

(37) |

102

(39) |

110

(43) |

113

(45) |

114

(46) |

108

(42) |

97

(36) |

86

(30) |

83

(28) |

114

(46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) |

65.8

(18.8) |

71.6

(22.0) |

79.9

(26.6) |

85.3

(29.6) |

92.0

(33.3) |

98.4

(36.9) |

103.7

(39.8) |

102.2

(39.0) |

97.3

(36.3) |

89.0

(31.7) |

75.5

(24.2) |

65.3

(18.5) |

104.9

(40.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) |

43.9

(6.6) |

48.9

(9.4) |

59.1

(15.1) |

68.3

(20.2) |

77.5

(25.3) |

87.9

(31.1) |

92.6

(33.7) |

91.0

(32.8) |

83.3

(28.5) |

70.8

(21.6) |

57.0

(13.9) |

45.8

(7.7) |

68.8

(20.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) |

33.2

(0.7) |

37.6

(3.1) |

47.4

(8.6) |

56.5

(13.6) |

66.7

(19.3) |

76.9

(24.9) |

81.5

(27.5) |

79.9

(26.6) |

71.7

(22.1) |

59.0

(15.0) |

45.8

(7.7) |

35.6

(2.0) |

57.7

(14.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) |

22.5

(−5.3) |

26.3

(−3.2) |

35.7

(2.1) |

44.8

(7.1) |

55.9

(13.3) |

65.9

(18.8) |

70.4

(21.3) |

68.8

(20.4) |

60.1

(15.6) |

47.2

(8.4) |

34.7

(1.5) |

25.4

(−3.7) |

46.5

(8.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) |

5.1

(−14.9) |

8.4

(−13.1) |

17.1

(−8.3) |

28.2

(−2.1) |

40.5

(4.7) |

53.9

(12.2) |

61.4

(16.3) |

59.3

(15.2) |

44.6

(7.0) |

29.7

(−1.3) |

17.9

(−7.8) |

8.4

(−13.1) |

1.0

(−17.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) |

−15

(−26) |

−22

(−30) |

−3

(−19) |

15

(−9) |

27

(−3) |

43

(6) |

51

(11) |

45

(7) |

31

(−1) |

14

(−10) |

1

(−17) |

−16

(−27) |

−22

(−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) |

0.85

(22) |

1.20

(30) |

2.30

(58) |

3.10

(79) |

5.17

(131) |

4.93

(125) |

3.98

(101) |

4.30

(109) |

3.05

(77) |

2.85

(72) |

1.36

(35) |

1.22

(31) |

34.31

(871) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) |

2.7

(6.9) |

3.6

(9.1) |

2.1

(5.3) |

0.2

(0.51) |

0.0

(0.0) |

0.0

(0.0) |

0.0

(0.0) |

0.0

(0.0) |

0.0

(0.0) |

0.2

(0.51) |

0.8

(2.0) |

3.1

(7.9) |

12.7

(32) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) |

4.8 |

5.3 |

7.4 |

8.3 |

11.3 |

9.5 |

8.3 |

8.2 |

6.9 |

6.6 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

87.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) |

2.7 |

2.2 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

2.2 |

9.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) |

69.9 |

68.3 |

63.8 |

62.8 |

67.0 |

64.3 |

58.9 |

61.1 |

66.8 |

65.1 |

70.0 |

71.7 |

65.8 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) |

19.6

(−6.9) |

23.7

(−4.6) |

32.0

(0.0) |

42.3

(5.7) |

53.1

(11.7) |

61.2

(16.2) |

63.7

(17.6) |

62.6

(17.0) |

56.8

(13.8) |

45.0

(7.2) |

34.0

(1.1) |

23.5

(−4.7) |

43.1

(6.2) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours |

190.9 |

186.4 |

230.4 |

257.8 |

289.8 |

305.0 |

342.1 |

309.2 |

245.6 |

226.3 |

170.2 |

168.7 |

2,922.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine |

62 |

62 |

62 |

65 |

66 |

69 |

76 |

73 |

66 |

65 |

56 |

57 |

66 |

| Average ultraviolet index |

2 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

7 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

6 |

| Source: National Weather Service (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[72][71][73] |

Pollen and other allergens

[edit]

Wichita is consistently ranked as one of the worst major cities in the nation for seasonal allergies, due largely to tree and grass pollen (partly from surrounding open plains and pastureland), and smoke from frequent burning of fields by the region's farmers and ranchers, driven by the strong Kansas winds.[74][75] The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, ranked Wichita—out of the nation's 100 largest cities—6th worst for people with allergies in 2016,[76] 3rd worst in 2021,[77] 2nd worst in 2022,[78] and worst nationwide in 2023.[74][79][80][81][82]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Main article: Neighborhoods of Wichita, Kansas

Downtown Wichita & Century II Convention Center along the Arkansas River

Downtown Wichita & Century II Convention Center along the Arkansas River

Wichita has several recognized areas and neighborhoods. The downtown area is generally considered to be east of the Arkansas River, west of Washington Street, north of Kellogg, and south of 13th Street. It contains landmarks such as Century II, the Garvey Center, and the Epic Center. Old Town is also part of downtown; this 50-acre (0.20 km2) area is home to a cluster of nightclubs, bars, restaurants, a movie theater, shops, and apartments and condominiums, many of which make use of historical warehouse-type spaces.

Two notable residential areas of Wichita are Riverside and College Hill. Riverside is northwest of downtown, across the Arkansas River, and surrounds the 120-acre (0.49 km2) Riverside Park.[83] College Hill is east of downtown and south of Wichita State University. It is one of the more historic neighborhoods, along with Delano on the west side and Midtown in the north-central city.[84]

Four other historic neighborhoods—developed in southeast Wichita (particularly near Boeing, Cessna and Beech aircraft plants) -- are among the nation's few remaining examples of U.S. government-funded temporary World War II housing developments to support war factory personnel: Beechwood (now mostly demolished), Oaklawn, Hilltop (the city's highest-density large neighborhood), and massive Planeview (where over 30 languages are spoken) -- in all, home to about a fifth of the city's population at their peak. Though designed as temporary housing, all have remained occupied into the 21st century, most becoming low-income neighborhoods.[85][86][89]

Demographics

[edit]

Main article: Demographics of Wichita, Kansas

Historical population

| Census |

Pop. |

Note |

%± |

| 1870 |

689 |

|

— |

| 1880 |

4,911 |

|

612.8% |

| 1890 |

23,853 |

|

385.7% |

| 1900 |

24,671 |

|

3.4% |

| 1910 |

52,450 |

|

112.6% |

| 1920 |

72,217 |

|

37.7% |

| 1930 |

111,110 |

|

53.9% |

| 1940 |

114,966 |

|

3.5% |

| 1950 |

168,279 |

|

46.4% |

| 1960 |

254,698 |

|

51.4% |

| 1970 |

276,554 |

|

8.6% |

| 1980 |

279,272 |

|

1.0% |

| 1990 |

304,011 |

|

8.9% |

| 2000 |

344,284 |

|

13.2% |

| 2010 |

382,368 |

|

11.1% |

| 2020 |

397,532 |

|

4.0% |

| 2023 (est.) |

396,119 |

[7] |

−0.4% |

In terms of population, Wichita is the largest city in Kansas and the 51st largest city in the United States, according to the 2020 census.[6]

Wichita has an extensive history of attracting immigrants. Starting in 1895, a population of Lebanese Americans moved to the city, many of whom were Orthodox Christians. A second wave of Lebanese migrants moved to Wichita to flee the Civil War in their homeland.[91] Thousands of immigrants from Vietnam moved to Wichita in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.[92]

Wichita, Kansas – Racial and ethnic composition

Note: the US census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos may be of any race.

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) |

Pop. 2000[93] |

Pop. 2010[94] |

Pop. 2020[95] |

% 2000 |

% 2010 |

% 2020 |

| White alone (NH) |

246,924 |

246,744 |

233,703 |

71.72% |

64.53% |

58.79% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) |

38,732 |

42,676 |

42,228 |

11.25% |

11.16% |

10.62% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) |

3,525 |

3,424 |

3,400 |

1.02% |

0.90% |

0.86% |

| Asian alone (NH) |

13,543 |

18,272 |

19,991 |

3.93% |

4.78% |

5.03% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) |

168 |

311 |

429 |

0.05% |

0.08% |

0.11% |

| Other race alone (NH) |

528 |

472 |

1,585 |

0.15% |

0.12% |

0.40% |

| Mixed race or multiracial (NH) |

7,752 |

12,121 |

23,410 |

2.25% |

3.17% |

5.89% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) |

33,112 |

58,348 |

72,786 |

9.62% |

15.26% |

18.31% |

| Total |

344,284 |

382,368 |

397,532 |

100.00% |

100.00% |

100.00% |

2020 census

[edit]

The 2020 United States census counted 397,532 people, 154,683 households, and 92,969 families in Wichita. The population density was 2,454.1 per square mile (947.5/km2). There were 172,801 housing units at an average density of 1,066.7 per square mile (411.9/km2).[96]

The U.S. census accounts for race by two methodologies. "Race alone" and "Race alone less Hispanics" where Hispanics are delineated separately as if a separate race.

The racial makeup (including Hispanics in the racial counts) was 63.39% (251,997) white, 10.95% (43,537) black or African-American, 1.33% (5,296) Native American, 5.09% (20,225) Asian, 0.12% (482) Pacific Islander, 7.41% (29,444) from other races, and 11.71% (46,551) from two or more races.[97]

The racial and ethnic makeup (where Hispanics are excluded from the racial counts and placed in their own category) was 58.79% (233,703) White (non-Hispanic), 10.62% (42,228) Black (non-Hispanic), 0.86% (3,400) Native American (non-Hispanic), 5.03% (19,991) Asian (non-Hispanic), 0.11% (429) Pacific Islander (non-Hispanic), 0.40% (1,585) from other race (non-Hispanic), 5.89% (23,410) from two or more races, and 18.31% (72,786) Hispanic or Latino.[95]

Of the 154,683 households, 26.6% had children under the age of 18; 42.6% were married couples living together; 29.4% had a female householder with no spouse present. 33.2% of households consisted of individuals and 11.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.5 and the average family size was 3.2.

24.6% of the population was under the age of 18, 9.5% from 18 to 24, 26.7% from 25 to 44, 23.2% from 45 to 64, and 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35.3 years. For every 100 females, the population had 97.5 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older, there were 95.7 males.

The 2016-2020 5-year American Community Survey[98] estimates show that the median household income was $53,466 (with a margin of error of +/- $1,028) and the median family income $69,930 (+/- $1,450). Males had a median income of $38,758 (+/- $1,242) versus $26,470 (+/- $608) for females. The median income for those above 16 years old was $31,875 (+/- $408). Approximately, 10.9% of families and 15.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.4% of those under the age of 18 and 8.7% of those ages 65 or over.

2010 census

[edit]

As of the census of 2010, 382,368 people, 151,818 households, and 94,862 families were residing in the city. The population density was 2,304.8 inhabitants per square mile (889.9/km2). The 167,310 housing units had an average density of 1,022.1 per square mile (394.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 71.9% White, 11.5% African American, 4.8% Asian, 1.2% American Indian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 6.2% from other races, and 4.3% from two or more races. Hispanics and Latinos of any race were 15.3% of the population.[99]

Of the 151,818 households, 33.4% had children under 18 living with them, 44.1% were married couples living together, 5.2% had a male householder with no wife present, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.5% were not families. About 31.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.48, and the average family size was 3.14.[99]

The median age in the city was 33.9 years; 26.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.1% were between 18 and 24; 26.9% were from 25 to 44; 24.9% were from 45 to 64; and 11.5% were 65 or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.3% male and 50.7% female.[99]

The median income for a household in the city was $44,477, and for a family was $57,088. Males had a median income of $42,783 versus $32,155 for females. The per capita income for the city was $24,517. About 12.1% of families and 15.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.5% of those under age 18 and 9.9% of those age 65 or over.[99]

Metropolitan area

[edit]

Main article: Wichita, KS Metropolitan Statistical Area

Wichita is the principal city of both the Wichita Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and the Wichita-Winfield Combined Statistical Area (CSA).[100][101] The Wichita MSA encompasses Sedgwick, Butler, Harvey, and Sumner counties and, as of 2010, had a population of 623,061, making it the 84th largest MSA in the United States.[100][102][103]

The larger Wichita-Winfield CSA also includes Cowley County and, as of 2013, had an estimated population of 673,598.[104] Nearby Reno County is not a part of the Wichita MSA or Wichita-Winfield CSA, but, were it included, it would add an additional population of 64,511 as of 2010.[105]

Economy

[edit]

Boeing plant in Wichita (2010): Boeing was once the largest employer in Wichita (as per a 2005 analysis), and aviation remains the city's largest industry.

Boeing plant in Wichita (2010): Boeing was once the largest employer in Wichita (as per a 2005 analysis), and aviation remains the city's largest industry.

It is the birthplace of famous restaurants such as White Castle and Pizza Hut.[106][107] A survey of well-known Kansas-based brands conducted by RSM Marketing Services and the Wichita Consumer Research Center showed many of the top-25 Kansas-based brands such as Koch, Coleman, Cessna, Pizza Hut, Beechcraft, Freddy's, and more are based in Wichita.[108]

Wichita's principal industrial sector is manufacturing, which accounted for 21.6% of area employment in 2003. Aircraft manufacturing has long dominated the local economy, and plays such an important role that it has the ability to influence the economic health of the entire region; the state offers tax breaks and other incentives to aircraft manufacturers.[109]

Healthcare is Wichita's second-largest industry, employing about 28,000 people in the local area. Since healthcare needs remain fairly consistent regardless of the economy, this field was not subject to the same pressures that affected other industries in the early 2000s. The Kansas Spine Hospital opened in 2004, as did a critical-care tower at Wesley Medical Center.[110] In July 2010, Via Christi Health, which is the largest provider of healthcare services in Kansas, opened a hospital that will serve the northwest area of Wichita. Via Christi Hospital on St. Teresa is the system's fifth hospital to serve the Wichita community.[111] In 2016, Wesley Healthcare opened Wesley Children's Hospital, the first and only children's hospital in the Wichita area.[112]

Thanks to the early 20th-century oil boom in neighboring Butler County, Kansas, Wichita became a major oil town, with dozens of oil-exploration companies and support enterprises. Most famous of these was Koch Industries, today a global natural-resources conglomerate. The city was also at one time the headquarters of the former Derby Oil Company, which was purchased by Coastal Corporation in 1988.

Koch Industries and Cargill, the two largest privately held companies in the United States,[113] both operate headquarters facilities in Wichita. Koch Industries' primary global corporate headquarters is in a large office-tower complex in northeast Wichita. Cargill Meat Solutions Div., at one time the nation's third-largest beef producer, is headquartered downtown. Other firms with headquarters in Wichita include roller-coaster manufacturer Chance Morgan, gourmet food retailer Dean & Deluca, renewable energy company Alternative Energy Solutions, and Coleman Company, a manufacturer of camping and outdoor recreation supplies. Air Midwest, the nation's first officially certificated "commuter" airline, was founded and headquartered in Wichita and evolved into the nation's eighth-largest regional airline prior to its dissolution in 2008.[114]

As of 2013, 68.2% of the population over the age of 16 was in the labor force; 0.6% was in the armed forces, and 67.6% was in the civilian labor force with 61.2% employed and 6.4% unemployed. The occupational composition of the employed civilian labor force was 33.3% in management, business, science, and arts; 25.1% in sales and office occupations; 17.2% in service occupations; 14.0% in production, transportation, and material moving; and 10.4% in natural resources, construction, and maintenance. The three industries employing the largest percentages of the working civilian labor force were educational services, health care, and social assistance (22.3%); manufacturing (19.2%); and retail trade (11.0%).[99]

The cost of living in Wichita is below average; compared to a U.S. average of 100, the cost of living index for the city is 84.0.[115] As of 2013, the median home value in the city was $117,500, the median selected monthly owner cost was $1,194 for housing units with a mortgage and $419 for those without, and the median gross rent was $690.[99]

Aircraft manufacturing

[edit]

Beechcraft Starship were built in Wichita from 1983 to 1995.

Beechcraft Starship were built in Wichita from 1983 to 1995.

From the early to late 20th century, aircraft pioneers such as Clyde Cessna, Emil Matthew "Matty" Laird, Lloyd Stearman, Walter Beech, Al Mooney and Bill Lear began aircraft-manufacturing enterprises that led to Wichita becoming the nation's leading city in numbers of aircraft produced, earning Wichita, in 1928, the 1929 title "Air Capital City" from the nation's Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce — a title the city would claim permanently.[13][116][117][118]

The aircraft corporations E. M. Laird Aviation Company (the nation's first successful commercial airplane manufacturer), Travel Air (started by Beech, Stearman, and Cessna), Stearman, Cessna, Beechcraft, and Mooney were all founded in Wichita between 1920 and early 1932.[116][117][118][14] By 1931, Boeing (of Seattle, Washington) had absorbed Stearman, creating "Boeing-Wichita", which would eventually grow to become Kansas' largest employer.[15][119][120] During World War II, employment peak at Boeing-Wichita was 29,795 in December 1943.[121]

Today, Cessna Aircraft Co. (the world's highest-volume airplane manufacturer) and Beechcraft remain based in Wichita, having merged into Textron Aviation in 2014, along with Learjet and Boeing's chief sub-assembly supplier, Spirit AeroSystems. Airbus maintains a workforce in Wichita, and Bombardier (parent company of Learjet) has other divisions in Wichita, as well. Over 50 other aviation businesses operate in the Wichita MSA, as well as over 350 suppliers and subcontractors to the local aircraft manufacturers. In total, Wichita and its companies have manufactured an estimated 250,000 aircraft since Clyde Cessna's first Wichita-built aircraft in 1916.[15][16][116][117][13]

In the early 2000s, a national and international recession combined with the after-effects of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks to depress the aviation subsector in and around Wichita. Orders for new aircraft plummeted, prompting Wichita's five largest aircraft manufacturers, Boeing Co., Cessna Aircraft Co., Bombardier Learjet Inc., Hawker Beechcraft, and Raytheon Aircraft Co.—to slash a combined 15,000 jobs between 2001 and 2004. In response, these companies began developing small- and mid-sized airplanes to appeal to business and corporate users.[110]

In 2007, Wichita built 977 aircraft, ranging from single-engine light aircraft to the world's fastest civilian jet; one-fifth of the civilian aircraft produced in United States that year, plus numerous small military aircraft.[117][16][122] In early 2012, Boeing announced it would be closing its Wichita plant by the end of 2013,[120][123] which paved the road for Spirit Aerosystems to open its plant (actually, the Boeing-Wichita factory, still producing the same aircraft assemblies for Boeing, but officially under a different corporation).[13][124]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Arts

[edit]

Wichita Art Museum (2012)

Wichita Art Museum (2012)

Wichita is home to several art museums and performing arts groups. The Wichita Art Museum is the largest art museum in the state of Kansas and contains 7,000 works in permanent collections.[125] The Ulrich Museum of Art at Wichita State University is a modern and contemporary art museum with over 6,300 works in its permanent collection.[126]

Music

[edit]

Wichita is the music hub of central Kansas, and draws major acts from around the world, performing at various concert halls, arenas, and stadiums around the area. Most major rock'n'roll and pop-music stars, and virtually all country music stars, perform there during their career.[citation needed]

Music Theatre Wichita, Wichita Grand Opera (both nationally renowned),[127] and the Wichita Symphony Orchestra perform regularly at the Century II Convention Hall downtown. Concerts are also regularly performed by the nationally noted schools of music at Wichita's two largest universities.[127][128]

The Orpheum Theatre, a classic movie palace built in 1922, serves as a downtown venue for smaller shows. The Cotillion, a special events facility built in 1960, serves a similar purpose as a music venue.

Events

[edit]

The Wichita River Festival has been held in the Downtown and Old Town areas of the city since 1972. It has featured events, musical entertainment, sporting events, traveling exhibits, cultural and historical activities, plays, interactive children's events, a flea market, river events, a parade, block parties, a food court, fireworks, and souvenirs for the roughly 370,000+ patrons who attend each year.[129] In 2011, the festival was moved from May to June because of rain during previous festivals. The Wichita River Festival has seen immense growth, with record numbers in 2016 and again in 2018.[130] Much of that growth is attributed to attractive musical acts at the festival.[131]

Wichita customarily holds major parades for the River Festival, Christmas season (shortly after Thanksgiving), Veterans Day, Juneteenth, and St. Patrick's Day.[132]

The annual Wichita Black Arts Festival, held in the spring, celebrates the arts, crafts, and creativity of Wichita's large African-American community. It usually takes place in Central-Northeast Wichita. A Juneteenth event and parade also are common annual events.

The annual Wichita Asian Festival, usually held at Century II in October, displays the native arts, crafts, cultural performances and foods of Wichita's large, diverse Asian community from the Middle East, Central and South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia. The event includes many varied performances of Asian music, dance, acrobatics and martial arts, talent pageant, and vendors of Asian arts and crafts.[133][134][135][136] Dozens of food vendors serve the cuisine of most Asian nations.[137][135][134]

The International Student Association at Wichita State University presents an annual international cultural exhibition and food festival, on the campus at WSU, providing an inexpensive sampling of global culture and cuisine to the general public.

One or more large Renaissance fairs occur annually, including the "RenFair" in conjunction with the "Kingdom of Calontir" of the SCA (Society for Creative Anachronism). The fairs vary in length from one day to a week, typically at Sedgwick County Park or Newman University.

The Wichita Public Library's Academy Awards Shorts program is reportedly the oldest annual, complete, free public screening outside of Hollywood of the full array of short films nominated for an Academy Award ("Oscar"). In late winter, shortly before the Academy Awards ceremonies, the films—including all nominated documentary, live action, and animated shorts—are presented, free, at the Library and in local theaters and other venues around Wichita. Wichita's former Congressman, Motion Picture Association President Dan Glickman, has served as honorary chair of the event, and some of the filmmakers have attended and visited with the audiences.[138][139][140][141][142][143]

The Tallgrass Film Festival has been held in downtown Wichita since 2003. It draws over 100 independent feature and short films from all over the world for three days each October. Notable people from the entertainment industry have attended the festival.[144]

Aviation-related events are common in the Wichita area, including air shows, fly-ins, air races, aviation conferences, exhibitions, and trade shows. The city's two main air shows, which are generally held in alternating years, are the city-sponsored civilian Wichita Flight Festival[145] (originally the "Kansas Flight Festival") and the military-sponsored McConnell Air Force Base Open House and Airshow.[146]

A wide range of car shows are also common in Wichita,[147][148][149][150] including the Blacktop Nationals,[151][152][153] the Automobilia show (claiming over 1,000 vehicles on display[154]),[155] and the Riverfest Classic Car Show,[156] each of which fill much of downtown Wichita.[152][155][156] Wichita is also home to the large Cars for Charities Rod & Custom Car Show (started in 1957 as the Darryl Starbird Show), one of the longest-running indoor car shows in the nation.[157][158][159][160]

Points of interest

[edit]

Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum, downtown Wichita (2008)

Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum, downtown Wichita (2008)

Kansas Aviation Museum, former Wichita Municipal Airport terminal from 1935 to 1951, southeast Wichita (2008)

Kansas Aviation Museum, former Wichita Municipal Airport terminal from 1935 to 1951, southeast Wichita (2008)

Museums and landmarks devoted to science, culture, and area history are located throughout the city. Several lie along the Arkansas River west of downtown, including the Exploration Place science and discovery center, the Mid-America All-Indian Center, the Old Cowtown living history museum, and The Keeper of the Plains statue and its associated display highlighting the daily lives of Plains Indians. The Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum in downtown Wichita occupies the original Wichita city hall, built in 1892. The museum contains artifacts that tell the story of Wichita and Sedgwick County starting from 1865 and continuing to the present day.[161] Nearby is the 1913 Sedgwick County Memorial Hall and Soldiers and Sailors Monument. East of downtown is the Museum of World Treasures and railroad-oriented Great Plains Transportation Museum. The Coleman Factory Outlet and Museum was at 235 N St. Francis street and was the home of the Coleman Lantern until it closed in 2018.[162] Wichita State University hosts the Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology. The Kansas Aviation Museum, housed in the Terminal and Administration building of the former Municipal Airport, is in southeast Wichita adjacent to McConnell Air Force Base. The Original Pizza Hut Museum is also located on the Wichita State University campus for pizza lovers and fans to visit.

The Sedgwick County Zoo in the northwest part of Wichita is the most popular outdoor tourist attraction in the state of Kansas, and is home to more than 2,500 animals representing 500 different species.[163] The zoo is next to Sedgwick County Park and the Sedgwick County Extension Arboretum.

Intrust Bank Arena is the city's primary event venue, featuring 22 suites, 2 party suites, 40 loge boxes and over 300 premium seats with a total potential capacity of over 15,000.[164] This arena in the middle of Wichita opened in January 2010.[165]

Located immediately east of downtown is Old Town, the city's entertainment district. In the early 1990s, developers transformed it from an old warehouse district into a mixed-zone neighborhood with residential space, nightclubs, restaurants, hotels, and museums.[166]

Moody's Skidrow Beanery, at 625 E. Douglas in what was to become Old Town, was one of the more famous places in Wichita in the 1960s. It was the scene of a nationally followed First Amendment struggle[167] and was visited by Allen Ginsberg in 1966 (the name had been changed to the Magic Theatre Vortex Art Gallery) where he first read his long poem "Wichita Vortex Sutra."

Wichita is also home to two major indoor shopping malls: Towne East Square, managed by Simon Property Group, and Towne West Square. Towne East is home to four anchor stores and has more than 100 tenants. Towne West Square, which was put into foreclosure in 2019,[168] was still operational as of 2021. The oldest mall, Wichita Mall, was for many years largely a dead mall, but has since been converted into office space.[169] There are also two large outdoor shopping centers, Bradley Fair (which hosts jazz concerts and art festivals) located on the city's northeast side and New Market Square located on the city's northwest side. Each establishment consists of over 50 stores spread out on several acres.

In 1936, the Wichita post office contained two oil-on-canvas murals, Kansas Farming, painted by Richard Haines and Pioneer in Kansas by Ward Lockwood. Murals were produced from 1934 to 1943 in the United States through the Section of Painting and Sculpture, later called the Section of Fine Arts, of the Treasury Department. The post office building became the Federal Courthouse at 401 N. Market Street and the murals are on display in the lobby.[170]

Wichita also has a number of parks and recreational areas such as Riverside Park, College Hill Park, and McAdams Park.

Libraries

[edit]

The Wichita Public Library is the city's library system, presently consisting of a central facility, the Advanced Learning Library in Delano and six branch locations in other neighborhoods around the city.[171] The library operates several free programs for the public, including special events, technology training classes, and programs specifically for adults, children, and families.[172] As of 2009, its holdings included more than 1.3 million books and 2.2 million items total.[173]

Sports

[edit]

Main article: Sports in Wichita, Kansas

Intrust Bank Arena, home to the Wichita Thunder of the ECHL, located in downtown Wichita (2010)

Intrust Bank Arena, home to the Wichita Thunder of the ECHL, located in downtown Wichita (2010)

Wichita is home to several professional, semi-professional, non-professional, and collegiate sports teams. Professional teams include the Wichita Thunder ice hockey team and the Wichita Force indoor football team. The Wichita Wind Surge, a Minor League Baseball team of the Double-A Central play at Riverfront Stadium on the site of the former Lawrence–Dumont Stadium.[174] Their 2020 debut was postponed by the COVID-19 pandemic.[175] In 2021, the team dropped down to the Double-A Central (From Triple-A) without having played a Triple-A game due to Major League Baseball's realignment of the minor leagues. The city hosts the Air Capital Classic, a professional golf tournament of the Korn Ferry Tour first played in 1990.

Defunct professional teams which used to play in Wichita include the Wichita Aeros and Wichita Wranglers baseball teams, the Wichita Wings indoor soccer team, the Wichita Wind (farm team to the Edmonton Oilers National Hockey League team in the early 1980s) and the Wichita Wild indoor football team. Semi-pro teams included the Kansas Cougars and Kansas Diamondbacks football teams.[176][177] Non-professional teams included the Wichita Barbarians rugby union team and the Wichita World 11 cricket team.[178][179]

Collegiate teams based in the city include the Wichita State University Shockers, Newman University Jets, and the Friends University Falcons. The WSU Shockers are NCAA Division I teams that compete in men's and women's basketball, baseball, volleyball, track and field, tennis, and bowling. The Newman Jets are NCAA Division II teams that compete in baseball, basketball, bowling, cross country, golf, soccer, tennis, wrestling, volleyball, and cheer/dance. The Friends Falcons compete in Region IV of the NAIA in football, volleyball, soccer, cross country, basketball, tennis, track and field, and golf.

Riverfront Stadium (left), Arkansas River and downtown Wichita (upper right) (2023)

Riverfront Stadium (left), Arkansas River and downtown Wichita (upper right) (2023)

Several sports venues are in and around the city. Intrust Bank Arena, downtown, is a 15,000-seat multi-purpose arena that is home to the Wichita Thunder. Lawrence–Dumont Stadium, just west of downtown, was a medium-sized baseball stadium that has been home to Wichita's various minor-league baseball teams over the years. It was also home to the minor-league National Baseball Congress and the site of the Congress's annual National Tournament.

Eck Stadium at Wichita State University in northeast Wichita (2005)

Eck Stadium at Wichita State University in northeast Wichita (2005)

Wichita Ice Arena, just west of downtown, is a public ice-skating rink used for ice-skating competitions. Century II has been used for professional wrestling tournaments, gardening shows, sporting-goods exhibitions, and other recreational activities. The WSU campus includes two major venues: Eck Stadium, a medium-sized stadium with a full-sized baseball field that is home to the WSU Shocker baseball team, and Charles Koch Arena, a medium-sized, dome-roofed circular arena with a collegiate basketball court that hosts the WSU Shocker basketball team. Koch Arena is also used extensively for citywide and regional high school athletic events, concerts, and other entertainments. Just north of the city is 81 Motor Speedway, an oval motor-vehicle racetrack used extensively for a wide range of car, truck, and motorcycle races, and other motorsports events. Neighboring Park City is home to Hartman Arena and the Sam Fulco Pavilions, a moderate-capacity low-roofed arena developed for small rodeos, horse shows, livestock competitions, and exhibitions.

Wichita is also home to two sports museums, the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame and the Wichita Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.[180][181]

Professional

[edit]

| Team |

Founded |

League |

Sport |

| Wichita Thunder |

1992 |

ECHL |

Ice hockey |

| Wichita Wind Surge |

2020 |

Double-A Central |

Baseball |

| Wichita Wings |

2019 |

MASL 2 |

Indoor soccer |

College

[edit]

| School |

School

nickname |

Level |

# of

teams |

| Wichita State University |

Shockers |

NCAA Division I |

15 |

| Newman University |

Jets |

NCAA Division II |

16 |

| Friends University |

Falcons |

NAIA |

15 |

Government

[edit]

See also: List of mayors of Wichita, Kansas

Wichita City Hall (2018)

Wichita City Hall (2018)

Under state statute, Wichita is a city of the first class.[182] Since 1917, it has had a council–manager form of government.[183] The city council consists of seven members popularly elected every four years with staggered terms in office. For representative purposes, the city is divided into six districts with one council member elected from each. The mayor is the seventh council member, elected at large. The council sets policy for the city, enacts laws and ordinances, levies taxes, approves the city budget, and appoints members to citizen commission and advisory boards.[184] It meets each Tuesday.[182] The city manager is the city's chief executive, responsible for administering city operations and personnel, submitting the annual city budget, advising the city council, preparing the council's agenda, and oversight of non-departmental activities.[183] As of 2024, the city council consists of Mayor Lily Wu, Brandon Johnson (District 1), Becky Tuttle (District 2), Mike Hoheisel (District 3), Dalton Glasscock (District 4), J.V. Johnston (District 5), and Maggie Ballard (District 6).[185] The city manager is Robert Layton.[186]

The Wichita Police Department, established in 1871, is the city's law enforcement agency.[187] With over 800 employees, including more than 600 commissioned officers, it is the largest law enforcement agency in Kansas.[188] The Wichita Fire Department, organized in 1886, operates 22 stations throughout the city. Organized into four battalions, it employs over 400 full-time firefighters.[189]

As the county seat, Wichita is the administrative center of Sedgwick County. The county courthouse is downtown, and most departments of the county government base their operations in the city.[190]

Many departments and agencies of the U.S. Government have facilities in Wichita. The Wichita U.S. Courthouse, also downtown, is one of the three courthouses of the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas.[191] The U.S. Air Force operates McConnell Air Force Base immediately southeast of the city.[192] The campus of the Robert J. Dole Department of Veterans Affairs Medical and Regional Office Center is on U.S. 54 in east Wichita.[193] Other agencies, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation,[194] Food and Drug Administration,[195] and Internal Revenue Service[196] among others, have offices around the city.

Wichita lies within Kansas's 4th U.S. Congressional District, represented since 2017 by Republican Ron Estes. For the purposes of representation in the Kansas Legislature, the city is in the 16th and 25th through 32nd districts of the Kansas Senate and the 81st, 83rd through 101st, 103rd, and 105th districts of the Kansas House of Representatives.[182]

Education

[edit]

Wichita East High School (2012)

Wichita East High School (2012)

Primary and secondary education

[edit]

With over 50,000 students, Wichita USD 259 is the largest school district in Kansas.[197] It operates more than 90 schools in the city including 12 high schools, 16 middle schools, 61 elementary schools, and more than a dozen special schools and programs.[198] Outlying portions of Wichita lie within suburban public unified school districts including Andover USD 385, Circle USD 375, Derby USD 260, Goddard USD 265, Haysville USD 261, Maize USD 266, and Valley Center USD 262. Some of these schools, despite being in other school districts, are within the Wichita city limits.[199]

There are more than 35 private and parochial schools in Wichita.[200] The Roman Catholic Diocese of Wichita oversees 16 Catholic schools in the city including 14 elementary schools and two high schools, Bishop Carroll Catholic High School and Kapaun Mt. Carmel High School.[201] The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod operates three Lutheran schools in the city, Bethany Lutheran School (Grades PK-5), Holy Cross Lutheran School (PK-8), and Concordia Academy (9-12).[202][203] There are also two Seventh-day Adventist schools in Wichita, Three Angels School (K-8) and Wichita Adventist Christian Academy (K-10).[204][205] Other Christian schools in the city are Calvary Christian School (PK-12), Central Christian Academy (K-10), Classical School of Wichita (K-12), Sunrise Christian Academy (PK-12), Trinity Academy (K-12), Wichita Friends School (PK-6), and Word of Life Traditional School (K-12). In addition, there is an Islamic school, Annoor School (PK-8), operated by the Islamic Society of Wichita. Unaffiliated private schools in the city include Wichita Collegiate School, The Independent School, and Northfield School of the Liberal Arts, as well as three Montessori schools.[206]

Colleges and universities

[edit]

Davis Administration Building at Friends University (2006)

Davis Administration Building at Friends University (2006)

Wichita has several colleges, universities, technical schools and branch campuses of other universities around the state. These include the following:

- Wichita State University

- Friends University

- Newman University

- University of Kansas - School of Medicine Wichita Campus (KU Wichita)

- Wichita Technical Institute

Three universities have their main campuses in Wichita. The largest is Wichita State University (WSU), a public research university classified by Carnegie as "R2: Doctoral Universities – Higher Research Activity." WSU has more than 14,000 students and is the third-largest university in Kansas.[207][208] WSU's main campus is in northeast Wichita with multiple satellite campuses around the metro area.[209] Friends University, a private, non-denominational Christian university, has its main campus in west Wichita as does Newman University, a private Catholic university.[210][211] Wichita Area Technical College, founded in 1995, was merged into Wichita State University's College of Applied Sciences and Technology in 2018, and is now known as WSU Tech.

Several colleges and universities based outside Wichita operate satellite locations in and around the city. The University of Kansas School of Medicine has one of its three campuses in Wichita.[212] Baker University, Butler Community College, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Southwestern College, Tabor College, Vatterott College, and Webster University have Wichita facilities as do for-profit institutions including Heritage College and University of Phoenix.[213][214][215][216]

[edit]

Main article: Media in Wichita, Kansas

The Wichita Eagle, which began publication in 1872, is the city's major daily newspaper.[217] It was founded and edited for forty years by Marshall Murdock (1837-1908), a major player in local and state Republican politics, as well as doubling as postmaster.[218] Colloquially known as The Eagle. In 1960, the Wichita Eagle purchased Beacon Newspaper Corp. After purchasing the paper, the Wichita Eagle begin publishing the Eagle, which was a morning and afternoon newspaper, and the Beacon which was the evening paper.[219] The Wichita Business Journal is a weekly newspaper that covers local business events and developments.[220] Several other newspapers and magazines, including local lifestyle, neighborhood, and demographically focused publications are also published in the city.[221] These include: The Community Voice, a weekly African American community newspaper;[222] El Perico, a monthly Hispanic community newspaper;[223][224] The Liberty Press, monthly LGBT news;[225] Splurge!, a monthly local fashion and lifestyle magazine;[226] The Sunflower, the Wichita State University student newspaper.[227] The Wichita media market also includes local newspapers in several surrounding suburban communities.

The Wichita radio market includes Sedgwick County and neighboring Butler and Harvey counties.[228] Six AM and more than a dozen FM radio stations are licensed to and/or broadcast from the city.[229]

Wichita is the principal city of the Wichita-Hutchinson, Kansas television market, which comprises the western two-thirds of the state.[230] All of the market's network affiliates broadcast from Wichita with the ABC, CBS, CW, FOX and NBC affiliates serving the wider market through state networks of satellite and translator stations.[231][232][233][234][235][236] The city also hosts a PBS member station, a Univision affiliate, and several low-power stations.[237][238]

Filmed in Wichita

[edit]

The 1980 horror film, The Attic, was set and filmed in Wichita.[239][240] Scenes from the films Mars Attacks! and Twister were filmed in Wichita.[241]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Flood control

[edit]

Wichita suffered severe floods of the Arkansas river in 1877, 1904, 1916, 1923, 1944, 1951 and 1955. In 1944 the city flooded 3 times in 11 days.[242] As a result of the 1944 flood, the idea for the Wichita-Valley Center Floodway (locally known as the "Big Ditch") was conceived. The project was completed in 1958. The Big Ditch diverts part of the Arkansas River's flow around west-central Wichita, running roughly parallel to the Interstate 235 bypass.[64][243] A second flood control canal lies between the lanes of Interstate 135, running south through the central part of the city. Chisholm Creek is diverted into this canal for most of its length.[64][244] The city's flood defenses were tested in the Great Flood of 1993. Flooding that year kept the Big Ditch full for more than a month and caused $6 million of damage to the flood control infrastructure. The damage was not fully repaired until 2007.[245] In 2019, the Floodway was renamed the MS Mitch Mitchell Floodway in honor of the man credited for its creation.[246]

Utilities

[edit]

Evergy provides electricity.[247] Kansas Gas Service provides natural gas.[248] The City of Wichita provide water and sewer.[249] Multiple privately owned trash haulers, licensed by the county government, offer trash removal and recycling service.[250] Cox Communications and Spectrum offer cable television, and AT&T U-Verse offers IPTV.[251] All three also offer home telephone and broadband internet service.[252] Satellite TV is offered by DIRECTV and DISH. Satellite internet is available from Viasat, Hughes, and soon Starlink.

Health care

[edit]

Ascension Via Christi operates three general medical and surgical hospitals in Wichita—Via Christi Hospital St. Francis, Via Christi Hospital St. Joseph, and Via Christi Hospital St. Teresa—and other specialized medical facilities.[253] The Hospital Corporation of America manages a fourth general hospital, Wesley Medical Center, along with satellite locations around the city.[254] All four hospitals provide emergency services. In addition, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs runs the Robert J. Dole VA Medical Center, a primary and secondary care facility for U.S. military veterans.[193]

Transportation

[edit]

Highway

[edit]

Interstate 135 begins at this exit from the Kansas Turnpike (Interstate 35) in south-central Wichita.

Interstate 135 begins at this exit from the Kansas Turnpike (Interstate 35) in south-central Wichita.

The average commute time in Wichita was 18.2 minutes from 2013 to 2017.[255] Several federal and state highways pass through the city. Interstate 35, as the Kansas Turnpike, enters the city from the south and turns northeast, running along the city's southeastern edge and exiting through the eastern part of the city. Interstate 135 runs generally north-south through the city, its southern terminus lying at its interchange with I-35 in south-central Wichita. Interstate 235, a bypass route, passes through north-central, west, and south-central Wichita, traveling around the central parts of the city. Both its northern and southern termini are interchanges with I-135. U.S. Route 54 and U.S. Route 400 run concurrently through Wichita as Kellogg Avenue, the city's primary east-west artery, with interchanges, from west to east, with I-235, I-135, and I-35. U.S. Route 81, a north–south route, enters Wichita from the south as Broadway, turns east as 47th Street South for approximately half a mile, and then runs concurrently north with I-135 through the rest of the city. K-96, an east–west route, enters the city from the northwest, runs concurrently with I-235 through north-central Wichita, turns south for approximately a mile, running concurrently with I-135 before splitting off to the east and traveling around northeast Wichita, ultimately terminating at an interchange with U.S. 54/U.S. 400 in the eastern part of the city. K-254 begins at I-235's interchange with I-135 in north-central Wichita and exits the city to the northeast. K-15, a north–south route, enters the city from the south and joins I-135 and U.S. 81 in south-central Wichita, running concurrently with them through the rest of the city. K-42 enters the city from the southwest and terminates at its interchange with U.S. 54/U.S. 400 in west-central Wichita.[64]

Bus

[edit]

Wichita Transit operates 53 buses on 18 fixed bus routes within the city. The organization reports over 2 million trips per year (5,400 trips per day) on its fixed routes. Wichita Transit also operates a demand response paratransit service with 320,800 passenger trips annually.[256] A 2005 study ranked Wichita near the bottom of the fifty largest American cities in terms of percentage of commuters using public transit. Only 0.5% used it to get to or from work.[257]

Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service northeast to Topeka and south to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Bus service is provided daily north towards Salina and west towards Pueblo, Colorado by BeeLine Express (subcontractor of Greyhound Lines).[258][259] The Greyhound bus station that was built in 1961 at 312 S Broadway closed in 2016, and services relocated 1 block northeast to the Wichita Transit station at 777 E Waterman.[260]

Air

[edit]

The Wichita Airport Authority manages the city's two main public airports, Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport and Colonel James Jabara Airport.[261] Located in the western part of the city, Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport is the city's primary airport as well as the largest airport in Kansas.[64][261] Seven commercial airlines (Alaska, Allegiant, American, Delta, Frontier, Southwest & United) serve Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport with non-stop flights to several U.S. airline hubs.[262] Jabara Airport is a general aviation facility on the city's northeast side.[263] The city also has several privately owned airports. Cessna Aircraft Field and Beech Factory Airport, operated by manufacturers Cessna and Beechcraft, respectively, lie in east Wichita.[264][265] Two smaller airports, Riverside Airport and Westport Airport, are in west Wichita.[266][267]

Rail

[edit]

Union Station, Wichita's former passenger rail station (2009)

Union Station, Wichita's former passenger rail station (2009)

Two Class I railroads, BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad (UP), operate freight rail lines through Wichita.[268] UP's OKT Line runs generally north-south through the city; north of downtown, the line consists of trackage leased to BNSF.[64][269] An additional UP line enters the city from the northeast and terminates downtown.[64] BNSF's main line through the city enters from the north, passes through downtown, and exits to the southeast, paralleling highway K-15.[64][270] The Wichita Terminal Association, a joint operation between BNSF and UP, provides switching service on three miles (5 km) of track downtown.[271] In addition, two lines of the Kansas and Oklahoma Railroad enter the city, one from the northwest and the other from the southwest, both terminating at their junction in west-central Wichita.[64]

Wichita has not had passenger rail service since 1979.[272] The nearest Amtrak station is in Newton 25 miles (40 km) north, offering service on the Southwest Chief line between Los Angeles and Chicago.[268] Amtrak offers bus service from downtown Wichita to its station in Newton as well as to its station in Oklahoma City, the northern terminus of the Heartland Flyer line.[273]

Walkability

[edit]

A 2014 study by Walk Score ranked Wichita 41st most walkable of fifty largest U.S. cities.[274]

Cycling

[edit]

After numerous citizen surveys showed Wichitans want better bicycle infrastructure, The Wichita Bicycle Master Plan, a set of guidelines toward the development of a 149-mile Priority Bicycle Network, was endorsed by the Wichita City Council on February 5, 2013, as a guide to future infrastructure planning and development. As a result, Wichita's bikeways covered 115 miles of the city by 2018. One-third of the bikeways were added between 2011, when the plan was still in development, and 2018.[275][276]

Notable people

[edit]

Main article: List of people from Wichita, Kansas

See also: List of Wichita State University people and List of Friends University people

In popular culture

[edit]

Wichita is mentioned in the 1968 hit song "Wichita Lineman" by Glen Campbell. It is also mentioned in the songs "I've Been Everywhere", and "Seven Nation Army".

Allen Ginsberg wrote about a visit to Wichita in his poem "Wichita Vortex Sutra", for which Philip Glass subsequently wrote a solo piano piece.[277]

The stage play Hospitality Suite takes place in Wichita as does its 1999 film adaptation, The Big Kahuna.[278] The city is the setting for the comic strip Dennis the Menace.[279]

The films Wichita (1955) and portions of Wyatt Earp (1994), both of which dramatize the life and career of former Wichita lawman Wyatt Earp, are set in Wichita,[280][281] as were early episodes of The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp (1955-1961),[282][283] the first adult-oriented western TV series.[284][285] The short-lived 1959–1960 television western Wichita Town was set during the city's early years.[286]

Other films wholly or partially set in the city include Good Luck, Miss Wyckoff (1979),[287] Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987),[288] The Ice Harvest (2005),[289] and Knight and Day (2010). In the 2016 remake of The Magnificent Seven, the lead character is identified as a Wichita lawman.[290][291]

Wichita's Old Cowtown Museum, a re-creation of early Wichita, has served as a setting for various western- and pioneer-themed films,[292] including two of the Sarah Plain and Tall trilogy.[293][294] A Wichita-area airport served as settings for The Gypsy Moths.[295][296]

Sister cities

[edit]

Cancún, Quintana Roo, Mexico - November 25, 1975[297]

Cancún, Quintana Roo, Mexico - November 25, 1975[297] Kaifeng, Henan, China - December 3, 1985[298]

Kaifeng, Henan, China - December 3, 1985[298] Orléans, Loiret, France - August 16, 1944,[299][300] through Sister Cities International

Orléans, Loiret, France - August 16, 1944,[299][300] through Sister Cities International Tlalnepantla de Baz, State of Mexico, Mexico[301]

Tlalnepantla de Baz, State of Mexico, Mexico[301]

See also

[edit]

Kansas portal

Kansas portal Cities portal

Cities portal United States portal

United States portal

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Sedgwick County, Kansas

- Abilene Trail

- Arkansas Valley Interurban Railway

- Joyland Amusement Park

- Wichita Public Schools

- McConnell Air Force Base

- USS Wichita, 3 ships

Notes

[edit]

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Wichita have been kept at various locations in and around the city from July 1888 to November 1953, and at the Mid-Continent Airport since December 1953 (currently named Wichita Dwight D. Eisenhower National Airport). For more information, see Threadex

References

[edit]

- ^ a b

Harris, Richard (2002). "The Air Capital Story: Early General Aviation & Its Manufacturers". In Flight USA.

- ^ "Travel Translator: Your guide to the local language in Wichita". VisitWichita.com. September 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f "Wichita, Kansas", Geographic Names Information System, United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior

- ^ "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Profile of Wichita, Kansas in 2020". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "QuickFacts; Wichita, Kansas; Population, Census, 2020 & 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Counties: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ United States Postal Service (2012). "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ "Wichita". CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Miner, Craig (Wichita State Univ. Dept. of History), Wichita: The Magic City, Wichita Historical Museum Association, Wichita, KS, 1988

- ^ Howell, Angela and Peg Vines, The Insider's Guide to Wichita, Wichita Eagle & Beacon Publishing, Wichita, KS, 1995

- ^ a b c d e f "We Built This City," September 2019, Air and Space Magazine, Smithsonian Institution, retrieved March 31, 2023

- ^ a b McCoy, Daniel (interview with Beechcraft CEO Bill Boisture), "Back to Beechcraft", Wichita Business Journal, February 22, 2013

- ^ a b c Harris, Richard, "The Air Capital Story: Early General Aviation & Its Manufacturers", reprinted from In Flight USA magazine on author's own website, 2002/2003

- ^ a b c Harris, Richard, (Chairman, Kansas Aviation Centennial; Kansas Aviation History Speaker, Kansas Humanities Council; Amer. Av. Historical Soc.), "Kansas Aviation History: The Long Story" Archived August 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 2011, Kansas Aviation Centennial website Archived December 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Grove Park Archaeological Site". Historic Preservation Alliance of Wichita and Sedgwick County. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Brooks, Robert L. "Wichitas". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ Sturtevant, William C. (1967). "Early Indian Tribes, Culture Areas, and Linguistic Stocks [Map]". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ The Munger House

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Kansas Territory". Kansapedia. Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Days of Darkness: 1820-1934". Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ a b Sowers, Fred A. (1910). "Early History of Wichita". History of Wichita and Sedgwick County, Kansas. Chicago: C.F. Cooper & Co. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ Elam, Earl H. (June 15, 2010). "Wichita Indians". Handbook of Texas (online ed.). Texas State Historical Association.

- ^ a b c d Howell, Angela; Vines, Peg (1995). The Insider's Guide to Wichita. Wichita, Kansas: Wichita Eagle & Beacon Publishing.

- ^ a b c "History of Wichita". Wichita Metro Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Midtown Neighborhood Plan" (PDF). Wichita-Sedgwick County Metropolitan Area Planning Department. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c Miner, Craig (1988). Wichita: The Magic City. Wichita, Kansas: Wichita Historical Museum Association.

- ^ "Oldtown History". OldtownWichita.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2009. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Delano's Colorful History". Historic Delano, Inc. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Wyatt Earp", American Experience history series, aired January 25, 2010, PBS, retrieved April 3, 2023